The Adventures of Norma

Words by Sandra Frey and Joanna Burgar

Photograph credit Joanna Burgar, Sandra Frey, and Max Goldmnan

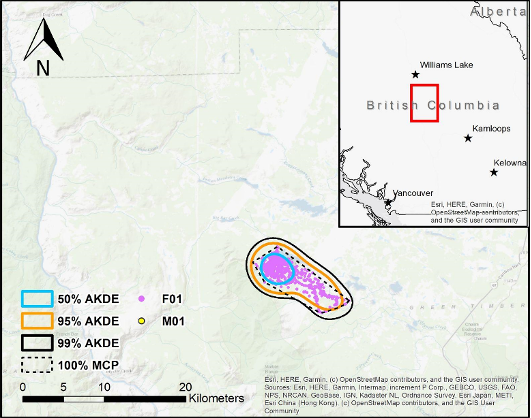

On February 18th 2024, a young female fisher (Pekania pennanti) by the name of Norma was captured in the central interior of British Columbia (B.C.), Canada and fit with a small GPS collar to track her movements over the next 30 days. This GPS collar would collect location data every 15 minutes to allow provincial biologists to better understand what kind of habitats fishers need for movement and foraging. Over the next month, Norma would cover more than 300 km within her 50 km² territory (Figure 1), shortly after which she gave birth to three kits in the cavity of a large aspen tree. Go Norma!

A young female fisher (“Norma”) was fit with a small GPS collar (not visible) to collect data on fisher movement and foraging habitat.

Norma’s GPS collar locations (pink dots) and estimated home range. Home range polygons are 100% minimum convex polygons (MCP), and 50-, 95- or 99% autocorrelated kernel density estimates (AKDE).

Norma’s Needs

Like other fishers, Norma relies on habitat features generally associated with mature forests (Photo 1). This includes large trees with cavities where females give birth and raise their young. Fishers also need habitat structures where they can safely rest when not on the move. This can include thick tree branches, nest-like structures formed in diseased spruce trees (i.e. “witches’ brooms”), and large pieces of woody debris on the forest floor. While older forests provide the habitat structures that fishers need for resting and reproduction, younger forests like those found regenerating stands can provide hunting grounds for snowshoe hare and other prey. But as a rule, fishers depend on forest canopy to feel safe, and they will rarely cross a forest opening that is wider than 50 m.

Female fishers like Norma rely on habitat structures typically associated with mature forests.

Large-diameter aspen tree with cavity openings where Norma gave birth to three kits.

Large pieces of coarse woody debris provide important ground resting habitat in winter.

Spruce tree with a large “witches’ broom” used by Norma as branch resting habitat.

The Endangered Columbian Population of Fishers

Norma belongs to the Columbian population of fishers, a genetically distinct population found only in central B.C. This population of fishers has been shrinking for decades, with ongoing habitat loss identified as the primary driver behind the decline. Due to the low number of remaining fishers in the landscape, the Columbian population of fishers was provincially listed as endangered in 2020.

Location points collected by Norma’s GPS collar will help us identify the habitats and types of forest stands that fishers select for movement and foraging. Fishers hunt small- to mid-sized prey like squirrels, grouse, snowshoe hare, and porcupine, which occupy different kinds of forest habitats. When selecting for hunting habitat, fishers must consider not just where there is a high abundance of prey but also environments in which that prey will be easier to catch. A fisher with access to good hunting grounds is a fisher that will likely live to see another day. And for a female fisher like Norma, being able to access and catch enough prey throughout the year also means that her body might be in good enough condition to give birth to a litter of 1-3 kits in early spring. Understanding what types and amounts of different habitats are found in the home range of a reproductive female fisher helps us understand what kind of habitats we need to keep on the landscape to support more fishers being produced to hopefully increase the number of individuals in this endangered population.

Knowing just how much habitat a fisher needs to survive also helps us better understand how many fishers the current landscapes of B.C. area able to support. In B.C., a female fisher will defend a 25-50 km² home range against other females. Males have an even larger home range of over 100 km² that they will share with females but exclude other males from overlapping. As a result of needing such a large footprint of habitat to survive and reproduce, fishers exist at very low population densities in the landscape and are therefore very sensitive to decline. And when we look at how human and climate-driven events such as logging, wildfire, and forest diseases such as mountain pine beetle have removed large swaths of fisher habitat from the landscape, it’s easier to understand why the Columbian fisher population is declining.

A Future for Fishers

Last fall, Norma’s three young kits likely dispersed to establish territories of their own. This will mean striking forth into the unknown to look for a large expanse of forested landscape containing enough good habitat (that is not already occupied by a resident fisher). Some might be killed by a predator or caught as incidental by-catch in a marten or lynx trap. But with a bit of luck, maybe one will be able to find a few thousand hectares of fisher habitat to call home and contribute to the next generation of Columbian fishers.

Acknowledgements: This work was conducted by the British Columbia Mesocarnivore Team (Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship) with support from the BC Trappers Association. All wildlife captures and handling were conducted under the appropriate wildlife and animal care permits, and supervised by wildlife veterinarian Malcolm McAdie. GPS location data processing and analysis was done by Jessica Buskirk and Katie Moriarty.